Research advance for uranium isotope as a quantitative proxy for paleo-oceans anoxic or oxic environment

-

摘要: 铀同位素因可定量反演全球尺度古海洋缺氧洋底分布面积占比(%)而被广泛应用在埃迪卡拉纪末期以来的重要大洋缺氧或生物事件中。通过对国内外相关文献进行综述,系统总结了利用铀同位素开展定量反演的原理、方法与成果,初步构建了铀同位素定量反演的还原性海洋洋底面积占比(%)与大气氧气浓度、大洋缺氧或生物事件的耦合关系,发现:(1)铀同位素反演结果与各缺氧或生物事件吻合度较高,表明铀同位素确实为有效的全球尺度深时尺度定量反演指标;(2)还原性海洋洋底扩张与大气氧气浓度变化之间普遍存在滞后性,推测与海平面、海洋生产力、海洋内部环流变化及底层水氧化还原反应的滞后性相关。指出铀同位素反演受样品后期成岩、风化蚀变作用的影响,可能存在解译误差;铀同位素单指标解译结果存在精准度偏低的缺点,需采用多指标综合反演的方法提升反演精度。Abstract:

Compared with other elements that are sensitive to redox environments (U, Mo, V, S, Fe, Cu, Zn, Ni), uranium isotopes have the advantage to quantitatively reflect long-term and global-scale paleoredox of oceans, due to its uniform composition in the oceans globally, and quantitative relationship with the proportion of the anoxic seafloor areas in ancient oceans. Therefore, uranium isotopes are widely used in the events such as the Late Ediacaran, Early Cambrian, Ordovician/Silurian, Late Devonian, Devonian/Carboniferous, Permian/Triassic, Triassic/Jurassic, and OAE 2 (Oceanic Anoxic Event 2). Through a review of previous papers, the author has systematically summarized the principles, methods, and results of using uranium isotopes for quantitative analysis of paleoredox. It has found that the core of current uranium isotopes quantitative method is the mass balance box model of seawater uranium (mass balance box model) and its isotopes and the related variants. By simplifying the uranium mass balance box model based on the proportion and fractionation coefficient of different types of uranium sinks, the redox environment and duration of ancient oceans can be quantitatively reflected. However, there may be ambiguity in the interpretation regarding whether the marine environment contains sulfur or not. In addition, by reviewing previous papers, the author has set up a preliminary coupling relationship among the proportion of anoxic seafloor area (%) reflected from uranium isotopes, atmospheric oxygen concentration, and oceanic anoxic or biological events. It has found that: (1) the uranium isotope analysis results were highly consistent with the occurrence time and extent of various anoxic or biological events, especially being coincident with the events that occurred in the Late Ediacaran, Late Ordovician, Late Devonian Frasnian-Famennian, Devonian/Carboniferous, Permian/Triassic, and Triassic/Jurassic periods, indicating that uranium isotopes are indeed an effective global scale and deep-time scale proxy for quantitative analysis on paleoredox of oceans. (2) The trend of anoxic seafloor expansion is not completely consistent with the trend of the atmospheric oxygen concentration changes. Usually, there is a lag. Only the trend of atmospheric oxygen concentration changes in the Triassic/Jurassic period is similar to the trend of oceanic redox environment changes. Analysis suggests that uranium isotope analysis results indicate the proportion of anoxic seafloor area, that is, the proportion of anoxic bottom seawater area, which is actually the change of redox environment of oceanic bottom water. At first, the change in atmospheric oxygen concentration affects shallow seawater, which first responds to the changes in the atmospheric redox environment, and then gradually affects the biological productivity of the seawater, gradually transmitting the environmental changes caused by redox evolution to the bottom water, and thus leading to a lag reaction of anoxic seafloor's expansion or shrink; or due to climatic changes, sea level rise and fall can cause changes of ocean internal circulation (such as thermohaline ocean circulation), leading to changes in productivity and causing anoxic seafloor area expansion or shrink, which may also result in hysteresis effects. There should be a kind of coupling relationship between the atmospheric redox evolution and ocean redox evolution, it deserves to be paid more attention for further study in future. In addition, through a review and analysis of previous research results, the author believes that there are several problems with the quantitative analysis of global scale paleoredox environments of oceans by using uranium isotopes, such as low accuracy, ambiguity, and the representativeness of samples. It is suggested to improve this method from the following two aspects further: (1) although uranium isotopes have been widely used in many important biological events or oceanic anoxic events since the Ediacaran period, the representativeness of sampling sites for some research results still needs to be improved. Although uranium isotopes are assumed to have global homogeneity theoretically, this assertion has not fully considered the influence of post-diagenesis, weathering and alteration in each sampling site on the uranium isotope composition that reflects the original seawater features. It is necessary to calibrate and verify the analysis results of different samples from different sampling sites of the same period to improve the quantitative analysis accuracy further. (2) The single proxy analysis results of uranium isotopes provides a wide range of anoxic seafloor area proportion, showing insufficient accuracy. It is necessary to carry out comprehensive multi-proxy isotopic quantitative analysis, by adding the results of isotopes like Mo, Tl, and others, which is believed could effectively improve the analysis accuracy for the same event. Finally, the author believes that if the accuracy of uranium isotopes method for quantitative analysis could be improved by comprehensive analysis with combination of other isotopes analysis, it is necessary to find out the coupling relationship between atmospheric redox evolution and marine redox evolution, especially the time effects of marine redox evolution to the atmospheric evolution. Hence, it is also possible to find out the response mechanism of oceanic redox conditions to the atmospheric redox evolution. The coupling relationship and the response mechanism may help the related researchers to predict the impact range and extent of oceanic redox evolution after a certain periods of lagging to the atmospheric redox evolution that is caused by natural and human factors. The results may provide great support for addressing global climate change. -

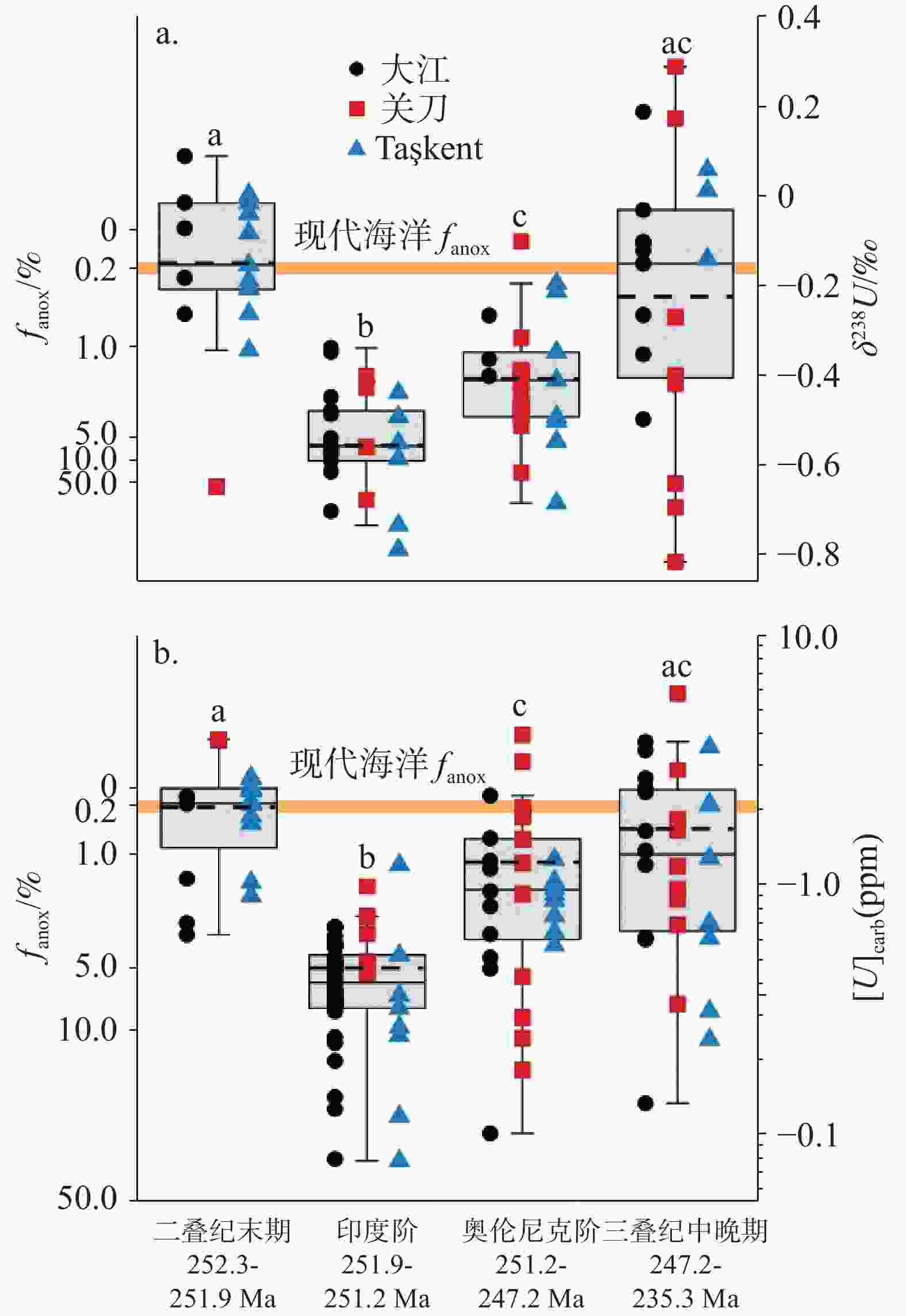

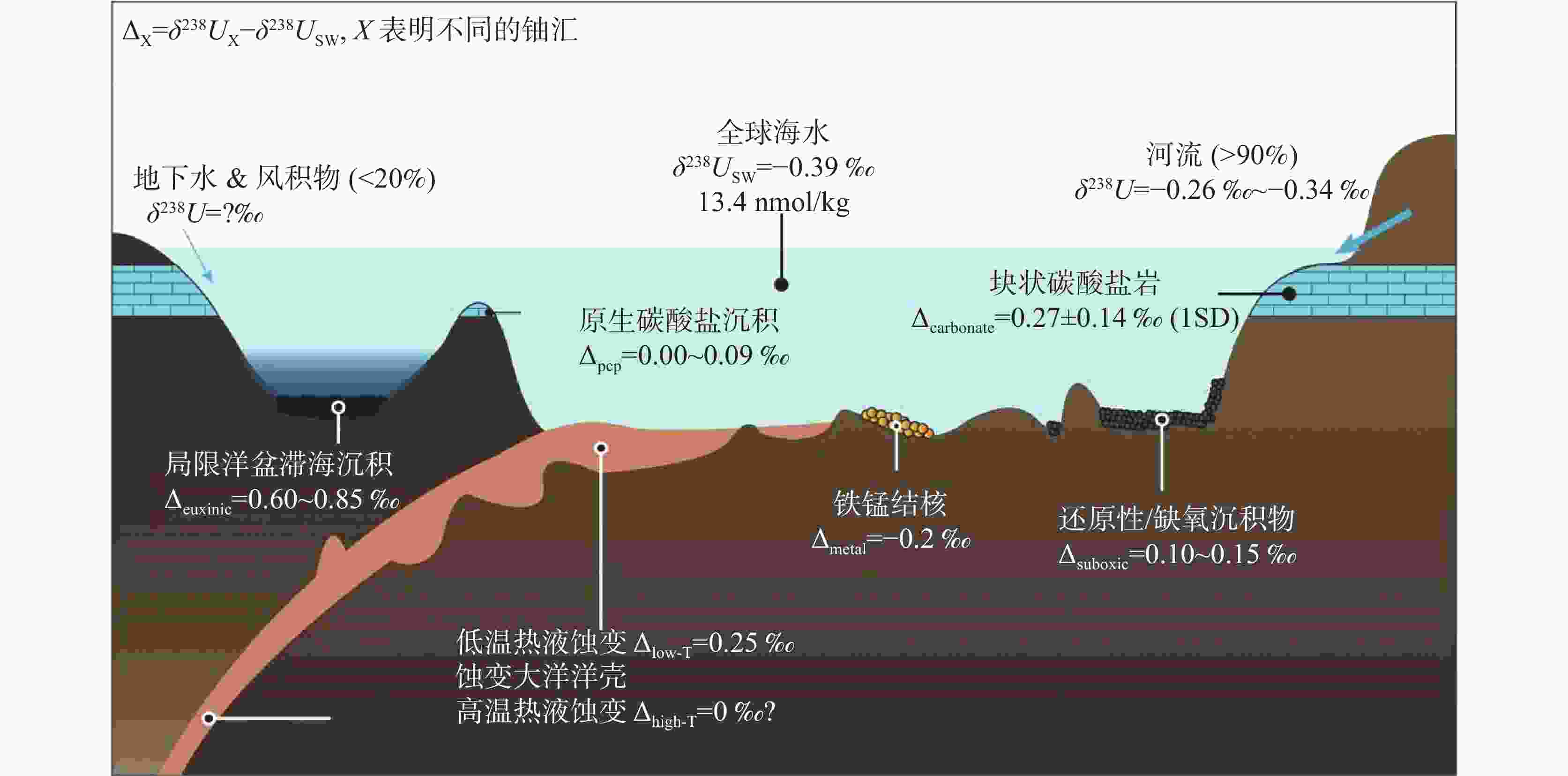

图 1 海洋中铀同位素平衡模型(海洋中主要的溶解铀来源于陆地河流,海洋铀会包括还原性/缺氧沉积物、局限性滞海洋盆沉积、海相碳酸盐、铁锰结核及蚀变大洋洋壳)(据[59])

Figure 1. U isotope budget model in the oceans (The main sources of dissolved uranium in the ocean are terrestrial rivers, and marine uranium can include reduced/anoxic sediments, localized stagnant ocean basin deposits, marine carbonates, ferromangan-manganese nodules, and altered macrocrust) (According to [59])

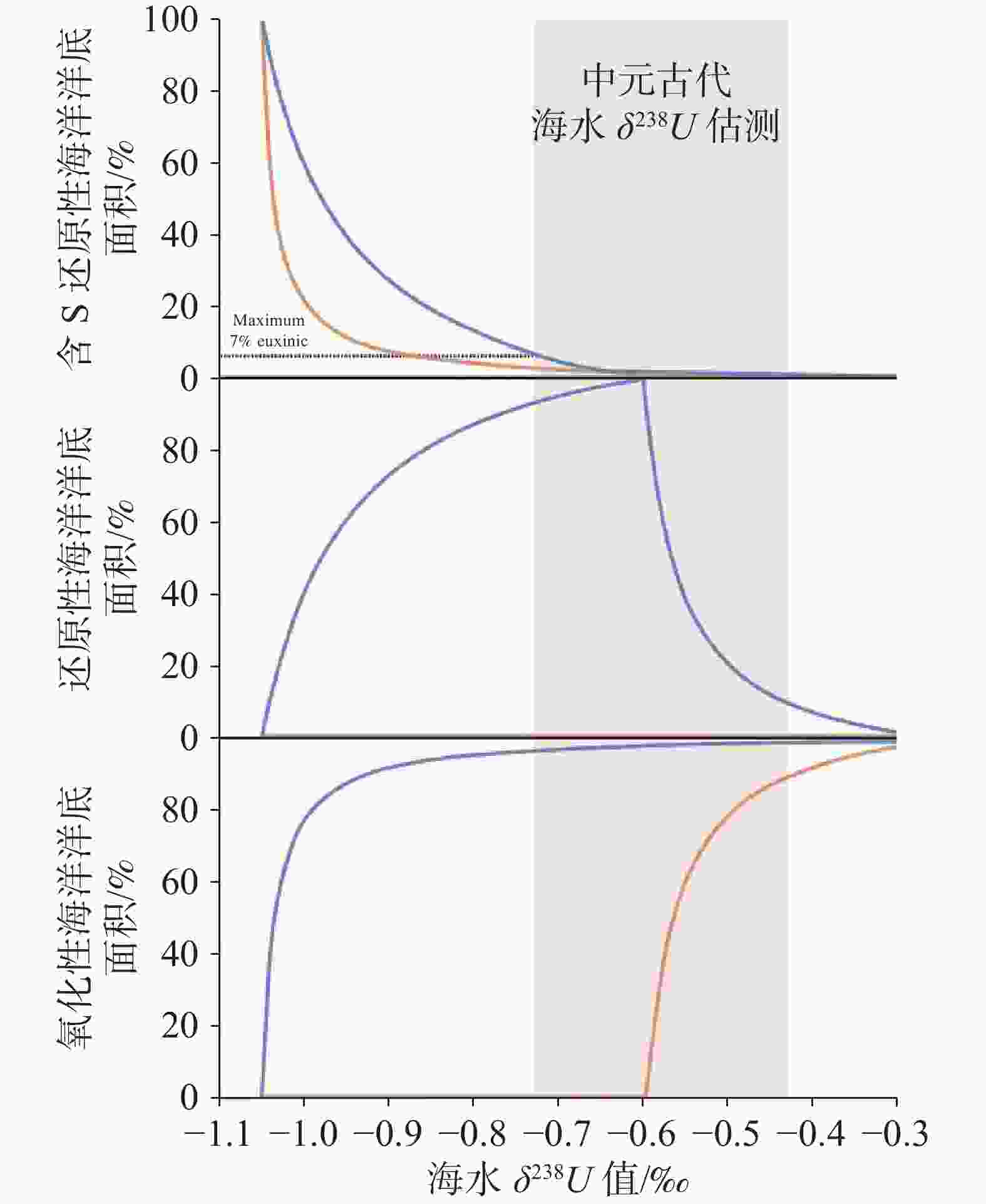

图 2 利用Lau铀汇箱式模型(A图:δ238U和B图:[U]值)计算出晚二叠纪-中晚三叠纪古海洋还原性面积占比fanox(据文献[37])

注:虚线为平均值,延长线上、下端为最大和最小值

Figure 2. Proportion of anoxic seafloor area (fanox, %) of Late Permian–Late-Middle Triassic by using Uranium Box Model (Figure A: δ238U and Figure B: [U] value) (According to literature[37])

Note: The dotted line is the average value, and the upper and lower ends of the extension line are the maximum and minimum values.

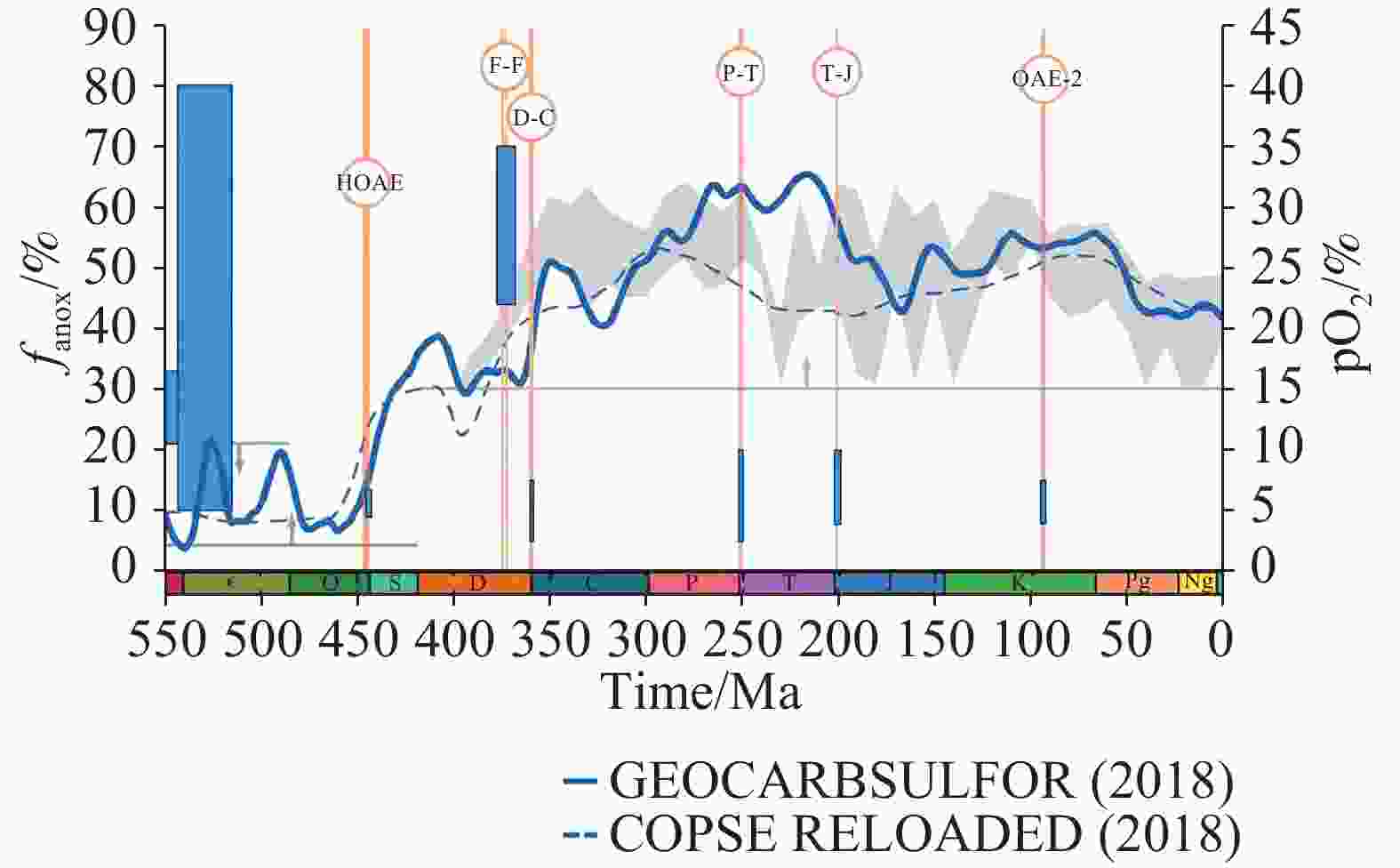

图 3 中元古代海洋三类铀汇质量守恒模型测算 (据文献[49])

橙线代表各种可能的模型迭代下的最小洋底面积,蓝色代表最大洋底面积,红色块状部分为中元古代海水δ238USW(–0.43%至–0.73‰),图中虚线交汇处,代表含S的还原性静海洋底面积占比最大为7%。

Figure 3. Estimation of three-sink mass balance modeling on Mid-Proterozoic seawater (According to literature [49])

The orange line represents the minimum seafloor area under various possible model iterations; the blue line represents the maximum seafloor area, and the red block represents the δ238USW (–0.43% to –0.73‰) of the Mesoproterozoic seawater. The intersection of dotted lines in the figure represents the maximum 7% of the seafloor area of the anoxic quiet sea containing S.

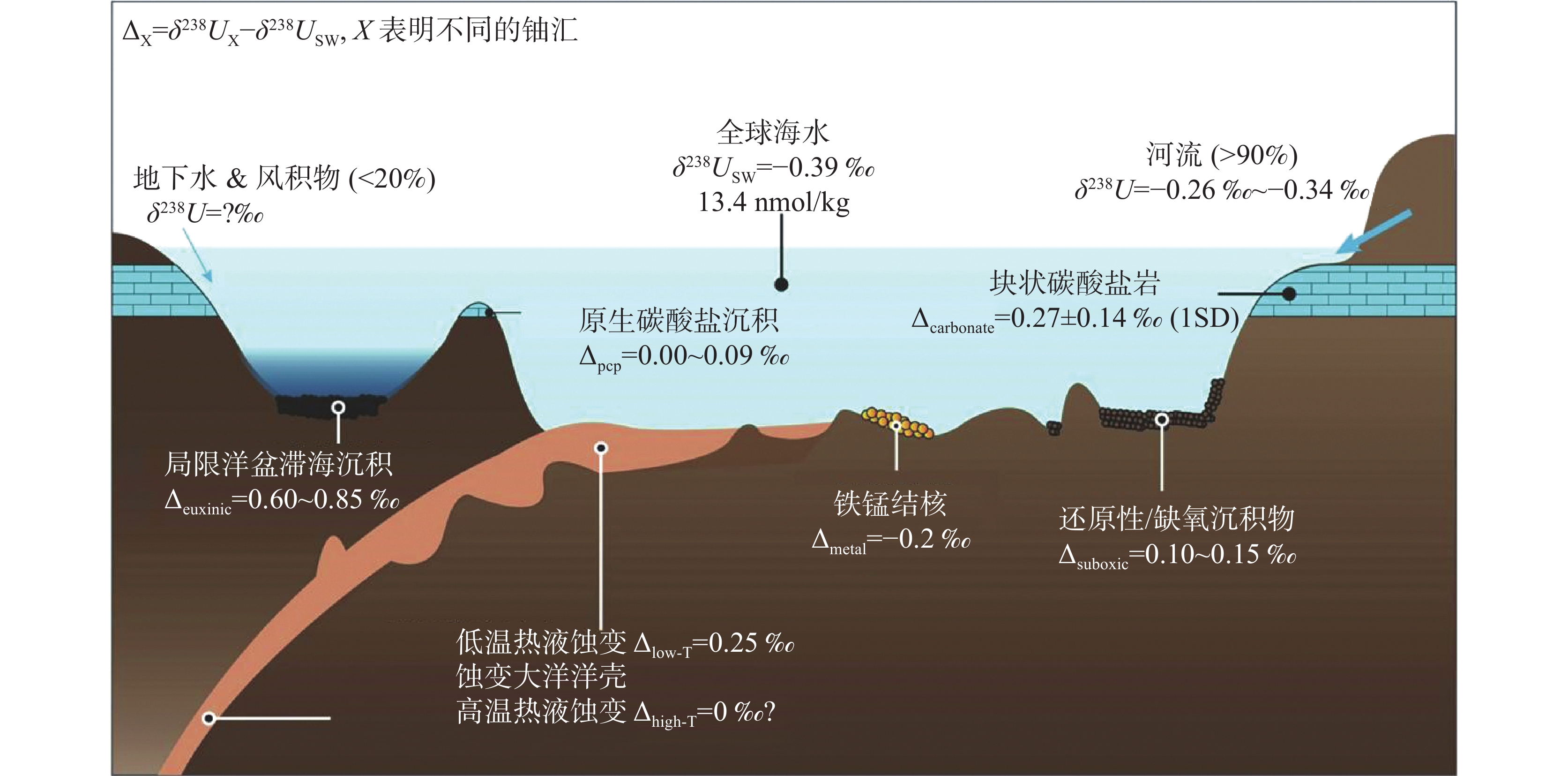

图 4 显生宙主要大洋缺氧事件(或生物大灭绝/生命大爆发事件)发生时期大气氧气浓度与还原性洋底面积占比变化耦合关系图(据[68]修改)

注:深蓝色实线为GEOCARBSULFOR生物地球化学模型模拟出的大气氧气含量变化范围[77];深蓝色虚线为COPSE生物地球化学模型模拟出的大气氧气含量变化范围[78];灰色不规则区域代表通过化石木炭重建的大气氧气含量变化曲线[79]。灰色线条代表通过地球化学指标、寒武纪生物群和大火燃烧记录重建的大气氧气浓度阈值[80−84]。浅蓝色方框代表对应年代还原性海洋洋底面积占比变化范围。

Figure 4. Coupling relationship between atmospheric oxygenation concentration, anoxic seafloor area (fanox, %) during the oceanic anoxic events (or mass extinction/life explosion) (Modified based on [68])

Note: The deep blue solid line represents the range of atmospheric oxygen content simulated by the GEOCARBSULFOR biogeochemical model [77]; the deep blue dashed line represents the range of atmospheric oxygen content simulated by the COPSE biogeochemical model[78]; the gray irregular region represents the curve of atmospheric oxygen content change reconstructed from fossil charcoal[79]. The gray lines represent the threshold values of atmospheric oxygen concentration reconstructed from geochemical indicators, Cambrian biota, and fire burning records[80−84]. The light blue box represents the range of the proportion of anoxic seafloor area for the corresponding period.

-

[1] Kaiho K, Kajiwara Y, Tazaki K, et al. Oceanic primary productivity and dissolved oxygen levels at the Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary: Their decrease, subsequent warming, and recovery[J]. Palaeoceanography, 1999, 14(4): 511-524. [2] Isozaki Y. Permian-Triassic boundary superanoxia and stratified superocean: Records from lost deep sea[J]. Science, 1997, 276: 235-238. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5310.235 [3] Bratton J F, Berry W B N, Morrow J R. Anoxia predates Frasnian-Famennian boundary mass extinction horizon in the Great Basin, USA[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 1999, 154: 275-292. doi: 10.1016/S0031-0182(99)00116-9 [4] Turgeon S C, Brumsack H J. Anoxic vs dysoxic events reflected in sediment geochemistry during the Cenomanian-Turonian Boundary Event (Cretaceous) in the Umbria-Marche Basin of Central Italy[J]. Chemical Geology, 2006, 234: 321-339. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2006.05.008 [5] 黄永建, 王成善, 顾健. 白垩纪大洋缺氧事件:研究进展与未来展望[J]. 地质学报, 2008, 82(1):21-30. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:0001-5717.2008.01.003HUANG Yongjian, WANG Chengshan, GU Jian. Cretaceous Oceanic Anoxic Events: Research progress and forthcoming prospects[J]. Acta Geologica Sinica, 2008, 82(1): 21-30. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:0001-5717.2008.01.003 [6] 陈曦, 郭会芳, 姚翰威, 韩凯博, 汪恒慧. 白垩纪大洋缺氧事件OAE2期间碳循环扰动的过程与机制[J]. 科学通报, 2022, 67(15):1677-1688.CHEN Xi, GUO Huifang, YAO Hanwei, HAN Kaibo, WANG Henghui. Processes and forcing mechanisms of the carbon cycle perturbation during Cretaceous Oceanic Anoxic Event 2[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2022, 67(15): 1677-1688. [7] 常华进, 储雪蕾, 冯连君, 黄晶, 张启锐. 氧化还原敏感微量元素对古海洋沉积环境的指示意义[J]. 地质论评, 2009, 55(1):91-99. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:0371-5736.2009.01.011CHANG Huajin, CHU Xuelei, FENG Lianjun, HUANG Jing, ZHANG Qirui. Redox sensitive trace elements as paleoenvironments proxies[J]. Geological Review, 2009, 55(1): 91-99. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:0371-5736.2009.01.011 [8] Clarkson M O, Stirling C H, Jenkynsb H C, et al. Uranium isotope evidence for two episodes of deoxygenation during Oceanic Anoxic Event 2[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2018, 115(12): 2918-2923. [9] Jenkyns H C. Geochemistry of Oceanic Anoxic Events[J]. Geochemistry Geophysics Geosystems, 2010, 11(3): Q03004. [10] Francois R. A study on the regulation of the concentrations of some trace metals (Rb, Sr, Zn, Pb, Cu, V, Cr, Ni, Mn and Mo) in Saanich Inlet Sediments, British Columbia, Canada[J]. Marine Geology, 1988, 83(1/2/3/4): 285-308. [11] Russell A D, Morford J L. The behavior of redox-sensitive metals across a laminated-massive-laminated transition in Saanich Inlet, British Columbia[J]. Marine Geology, 2001, 174(1/2/3/4): 341-354. [12] Algeo T J. Can marine anoxic events draw down the trace element inventory of seawater?[J]. Geology, 2004, 32: 1057-1060. [13] Calvert S E, Pedersen T F. Geochemistry of recent oxic and anoxic marine sediments: Implications for the geological record[J]. Marine Geology, 1993, 113(1/2): 67-88. [14] Piper D Z, Perkins R B. A modern vs. Permian black shale: The hydrography, primary productivity, and water-column chemistry of deposition[J]. Chemical Geology, 2004, 206(3/4): 177-197. [15] Morse J W, Luther G W III. Chemical influences on trace metal-sulfide interactions in anoxic sediments[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1999, 63(19/20): 3373-3378. [16] Grosjean E, Adam P, Connan J, Albrecht P. Effects of weathering on nickel and vanadyl porphyrins of a Lower Toarcian shale of the Paris basin[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2004, 68(4): 789-804. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(03)00496-4 [17] Wanty R B, Goldhaber M B. Thermodynamics and kinetics of reactions involving vanadium in natural systems: Accumulation of vanadium in sedimentary rocks[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1992, 56 (4): 1471-1483. [18] Morford J L, Emerson S. The geochemistry of redox sensitive trace metals in sediments[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1999, 63 (11/12): 1735-1750. [19] Tyson R V, Pearson T H. Modern and ancient continental shelf anoxia: An overview[J]. Geological Society, London, Spec Publications, 1991, 58: 1-24. doi: 10.1144/GSL.SP.1991.058.01.01 [20] Hatch J R, Leventhal J S. Relationship between inferred redox potential of the depositional environment and geochemistry of the Upper Pennsylvanian (Missourian) Stark Shale Member of the Dennis Limestone, Wabaunsee County, Kansas, U. S. A.[J]. Chemical Geology, 1992, 99: 65-82. doi: 10.1016/0009-2541(92)90031-Y [21] Bryn Jones, David A C Manning. Comparison of geochemical indices used for the interpretation of palaeoredox conditions in ancient mudstones[J]. Chemical Geology, 1994, 111: 111-129. doi: 10.1016/0009-2541(94)90085-X [22] Wignall P B. Black Shale[M]. Oxford: Claredon Press, 1994. [23] 周炼, 苏洁, 黄俊华, 颜佳新, 解习农, 高山, 戴梦宁, 腾格尔. 判识缺氧事件的地球化学新标志—钼同位素[J]. 中国科学:地球科学, 2011, 41(3):309-319. [24] 尚墨翰, 汤冬杰, 史晓颖, 魏昊明, 刘安琪. I/(Ca+Mg)作为指示碳酸盐沉积氧化还原条件的重要指标:研究进展与问题评述[J]. 古地理学报, 2018, 20(4):651-664. doi: 10.7605/gdlxb.2018.04.047SHANG Mohan, TANG Dongjie, SHI Xiaoying, WEI Haoming, LIU Anqi. I/(Ca+Mg) as an important redox proxy for carbonate sedimentary environments: Progress and problems[J]. Journal of Palaeogeography, 2018, 20(4): 651-664. doi: 10.7605/gdlxb.2018.04.047 [25] 张俊鹏, 李超, 张元动. 早古生代海洋缺氧事件的地质记录与背景机制[J]. 科学通报, 2022, 67(15):1644-1659.ZHANG Junpeng, LI Chao, ZHANG Yuandong. Geological evidences and mechanisms for oceanic anoxic events during the Early Paleozoic[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2022, 67(15): 1644-1659. [26] Kabanov P, Hauck T E, Gouwy S A, Grasby S E, Boon A v d. Oceanic anoxic events, marine photic-zone euxinia, and controversy of sea-level fluctuations during the Middle-Late Devonian[J]. Earth-Science Reviews, 2023, 241: 104415. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2023.104415 [27] 李聪颖, 吴思璠. 大洋缺氧事件金属稳定同位素研究进展[J]. 地球科学进展, 2022, 37(11):1127-1140. doi: 10.11867/j.issn.1001-8166.2022.085LI Congying, WU Sifan. Advances in research on stable metal isotopes in Oceanic Anoxic Events[J]. Advances in Earth Science, 2022, 37(11): 1127-1140. doi: 10.11867/j.issn.1001-8166.2022.085 [28] Dickson A J. A molybdenum-isotope perspective on Phanerozoic deoxygenation events[J]. Nature Geoscience, 2017, 10: 721-726. [29] Pearce C R, Cohen A S, Coe A L, Burton K W. Molybdenum isotope evidence for global ocean anoxia coupled with perturbations to the carbon cycle during the Early Jurassic[J]. Geology, 2008, 36(3): 231-234. doi: 10.1130/G24446A.1 [30] 王欢, 姚军明, 李杰. 钼同位素地球化学研究进展及其在成矿作用研究中的应用潜力[J]. 地球化学, 2019, 48(3):213-229.WANG Huan, YAO Junming, LI Jie. A review of progress in molybdenum isotope geochemistry and itspotential application in mineralization research[J]. Geochimica, 2019, 48(3): 213-229. [31] Ostrander C M, Owens J D, Nielsen S G. Constraining the rate of oceanic deoxygenation leading up to a Cretaceous Oceanic Anoxic Event (OAE-2:~94 Ma)[J]. Science Advances, 2017, 3: e1701020. [32] Weyer S, Anbar A D, Gerdes A, Gordon G W, Algeo T J, Boyle E A. Natural fractionation of 238U/235U[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2008, 72: 345-359. [33] 徐林刚. 238U/235U分馏及其地质应用[J]. 矿床地质, 2014, 33(3):497-510.XU Lingang. 238U/235U isotope fractionation in nature and its geological applications[J]. Mineral Deposits, 2014, 33(3): 497-510. [34] Dunk R M, Mills R A, Jenkins W J. A reevaluation of the oceanic uranium budget for the Holocene[J]. Chemical Geology, 2002, 190: 45-67. [35] Romaniello S J, Herrmann A D, Anbar A D. Uranium concentrations and 238U/235U isotope ratios in modern carbonates from the Bahamas: Assessing a novel paleoredox proxy[J]. Chemical Geology, 2013, 362: 305-316. [36] Tissot F L H, Dauphas N. Uranium isotopic compositions of the crust and ocean: Age corrections, U budget and global extent of modern anoxia[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2015, 167: 113-143. [37] Lau K V, Maher K, Altiner D, et al. Marine anoxia and delayed Earth system recovery after the end-Permian extinction[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2016, 113: 2360-2365. [38] Zhang F F, Algeo T J, Romaniello S J, et al. Congruent Permian-Triassic δ238U records at Panthalassic and Tethyan sites: Confirmation of global-oceanic anoxia and validation of the U-isotope paleoredox proxy[J]. Geology, 2018, 46(4): 327-330. [39] Cheng K, Elrick M, Romaniello S J. Early Mississipian ocean anoxia triggered organic carbon burial and late Paleozoic cooling: Evidence from uranium isotopes recorded in marine limestone[J]. Geology, 2020, 48(4): 363-367. [40] Stirling C H, Andersen M B, Potter E K, Halliday A N. Low-temperature isotopic fractionation of uranium[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2007, 264: 208-225. [41] Andersen M B, Romaniello S, Vance D, Little S H, Herdman R, Lyons T W. A modern framework for the interpretation of 238U/235U in studies of ancient ocean redox[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2014, 400: 184-194. [42] Chen X M, Romaniello S J, Herrmann A D, Wasylenki L E, Anbar A D. Uranium isotope fractionation during coprecipitation with aragonite and calcite[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2016, 188: 189-207. [43] Chen X M, Romaniello S J, Hermann A D, Samankassou E, Anbar A D. Biological effects on uranium isotope fractionation (238U/235U) in primary biogenic carbonates[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2018, 240: 1-10. [44] Tissot F L H, Chen C, Go B M, et al. Controls of eustasy and diagenesis on the 238U/235U of carbonates and evolution of the seawater (234U/238U) during the last 1.4 Myr[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2018, 242: 233-265. [45] Brennecka G A, Herrmann A D, Algeo T J, Anbar A D. Rapid expansion of oceanic anoxia immediately before the end Permian mass extinction[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2011, 108: 17631-17634. [46] Dahl T W, Boyle R A, Canfield D E, Connelly J N, Gill B C, Lenton T M, Bizzarro M. Uranium isotopes distinguish two geochemically distinct stages during the later Cambrian SPICE event[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2014, 401: 313-326. [47] Dahl T W, Connelly J N, Kouchinsky A, Gill B C, Månsson S F, Bizzarro M. Reorganisation of Earth's biogeochemical cycles briefly oxygenated the oceans 520 Myr ago[J]. Geochemical Perspective Letters, 2017, 3(2): 210-220. [48] Elrick M, Polyak V, Algeo T J, et al. Globalocean redox variation during the middle late Permian through Early Triassic based on uranium isotope and Th/U trends of marine carbonates[J]. Geology, 2017, 45: 163-166. [49] Gilleaudeau G J, Romaniello S J, Luo G M, et al. Uranium isotope evidence for limited euxinia in mid-Proterozoic oceans[J]. Earth and Planetary Science letters, 2019, 521: 150-157. [50] Zhang F, Lenton T M, Rey A, et al. Uranium isotopes in marine carbonates as a global ocean paleoredox proxy: A critical review[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2020, 287: 27-49. [51] Andersen M B, Stirling C H, Weyer S. Uranium isotope fractionation[J]. Reviews in Mineralogy & Geochemistry, 2017, 82: 799-850. [52] Morford J L, Emerson S. The geochemistry of redox sensitive trace metals in sediments[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1999, 63: 1735-1750. [53] Andersen M B, Vance D, Morford J L, et al. Closing in on the marine 238U/235U budget[J]. Chemical Geology, 2016, 420: 11-22. [54] Holmden C, Amini M, Francois R. Uranium isotope fractionation in Saanich Inlet: A modern analog study of a paleoredox tracer[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2015, 153: 202-215. [55] Rolison J M, Stirling C H, Middag R, et al. Uranium stable isotope fractionation in the Black Sea: Modern calibration of the 238U/235U paleo-redox proxy[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2017, 203: 69-88. [56] Zhang F F, Xiao S H, Kendall B, et al. Extensive marine anoxia during the terminal Ediacaran Period[J]. Science Advances, 2018, 4: eaan8983. [57] Goto K T, Anbar A D, Gordon G W, et al. Uranium isotope systematics of ferromanganese crusts in the Pacific Ocean: Implications for the marine 238U/235U isotope system[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2014, 146: 43-58. [58] Wang X L, Planavsky N J, Reinhard C T, Hein J R, Johnson T M. A Cenozoic Seawater redox record derived from 238U/235U in ferromanganese crusts[J]. American Journal of Science, 2016, 316(1): 64-83. [59] Zhang F, Dahl T W, Lenton T M, et al. Extensive marine anoxia associated with the Late Devonian Hangenberg Crisis[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2020, 533: 115976. [60] Helly J J, Levin L A. Global distribution of naturally occurring marine hypoxia on continental margins[J]. Deep Sea Research Part I-Oceanographic Research Papers, 2004, 51(9): 1159-1168. [61] Montoya-Pino C, Weyer S, Anbar A D, et al. Global enhancement of ocean anoxia during Oceanic Anoxic Event 2: A quantitative approach using U isotopes[J]. Geology, 2010, 38(4): 315-318. [62] Maher K, Steefel C I, DePaolo D J, et al. The mineral dissolution rate conundrum: Insights from reactive transport modeling of U isotopes and pore fluid chemistry in marine sediments[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2006, 70(2): 337-363. [63] Payne J L, Kump L. Evidence for recurrent Early Triassic massive volcanism from quantitative interpretation of carbon isotope fluctuations[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2007, 256(1-2): 264-277. [64] Winguth C, Winguth A M E. Simulating Permian-Triassic oceanic anoxia distribution: Implications for species extinction and recovery[J]. Geology, 2012, 40(2): 127-130. [65] Burgess S D, Bowring S, Shen S Z. High-precision timeline for Earth's most severe extinction[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2014, 111(9): 3316-3321. [66] Stylo M, Neubert N, Wang Y, et al. Uranium isotopes fingerprint biotic reduction[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2015, 112(18): 5619-5624. [67] Noordmann J, Weyer S, Georg R B, et al. 238U/235U isotope ratios of crustal material, rivers and products of hydrothermal alteration: New insights on the oceanic U isotope mass balance[J]. Isotopes in Environmental and Health Studies, 2015, 18: 1-23. [68] Reershemius T, Planavsky N J. What controls the duration and intensity of ocean anoxic events in the Paleozoic and the Mesozoic?[J]. Earth-Science Review, 2021, 221: 103787. [69] Tostevin R, Clarkson M O, Gangl S, et al. Uranium isotope evidence for an expansion of anoxia in terminal Ediacaran oceans[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2019, 506: 104-112. doi: 10.1016/j.jpgl.2018.10.045 [70] Wei G, Planvasky N J, Tarhan L G, et al. Marine redox fluctuation as a potential trigger for the Cambrian explosion[J]. Geology, 2018, 46: 587-590. [71] Wei G, Planvasky N J, He T, et al. Global marine redox evolution from the late Neoproterozoic to the early Paleozoic constrained by the integration of Mo and U isotope records[J]. Earth-Science Reviews, 2021, 214: 103506. [72] Dahl T W, Connelly J N, Kouchinsky A. Atmosphere−ocean oxygen and productivity dynamics during early animal radiations[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2019, 116(39): 19352-19361. [73] Bartlett R, Elrick M, Wheeley J R, et al. Abrupt global-ocean anoxia during the Late Ordovician-early Silurian detected using uranium isotopes of marine carbonates[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2018, 115: 5896-5901. [74] White D A, Elrick M, Romaniello S, et al. Global seawater redox trends during the Late Devonian mass extinction detected using U isotopes of marine limestones[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2018, 503: 68-77. [75] Zhang F F, Shen S Z, Cui Y, et al. Two distinct peisodes of marine anoxia during the Permian-Triassic crisis evidences by uranium isotopes in marine dolostones[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2020, 287: 165-179. [76] Jost A B, Bachan A, Schootbrugge B, et al. Uranium isotope evidence for an expansion of marine anoxia during the end-Triassic extinction[J]. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 2017, 18: 3093-3108. doi: 10.1002/2017GC006941 [77] Krause A J, Mills B J W, Zhang S, et al. Stepwise oxygenation of the Paleozoic atmosphere[J]. Nature Communications, 2018, 9: 4081. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06383-y [78] Lenton T M, Daines S J, Mills B J W. COPSE reloaded: An improved model of biogeochemical cycling over Phanerozoic time[J]. Earth-Science Reviews, 2018, 178: 1-28. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.12.004 [79] Glasspool I J, Scott A C. Phanerozoic concentrations of atmospheric oxygen reconstructed from sedimentary charcoal[J]. Nature Geoscience, 2010, 3: 627-630. [80] Sperling E A, Wolock C J, Morgan A S, et al. Statistical analysis of iron geochemical data suggests limited late Proterozoic oxygenation[J]. Nature, 2015, 523 (7561): 451-454. [81] Belcher C M, McElwain J C. Limits for combustion in low O2 redefine paleoatmospheric predictions for the Mesozoic[J]. Science, 2008, 321: 1197-1201. doi: 10.1126/science.1160978 [82] Glasspool I J, Scott A C, Waltham D, et al. The impact of fire on the Late Paleozoic Earth system[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2015, 6: 1-13. [83] Canfield D E. A new model for Proterozoic ocean chemistry[J]. Nature, 1998, 396: 450-453. doi: 10.1038/24839 [84] Canfield D E. In: Holland H D, Turekian, K K (Eds.). Treatise on Geochemistry[M]. New York: Elsevier, 2014: 197−216. -

下载:

下载: